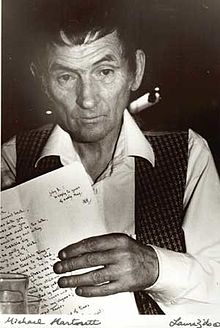

Michael Hartnett (Irish: Mícheál Ó hAirtnéide) (18 September 1941 – 13 October 1999) was an Irish poet who wrote in both English and Irish. He was one of the most significant voices in late 20th-century Irish writing and has been called “Munster‘s de facto poet laureate”.[1]

Hartnett was born in Croom Hospital, County Limerick.[2] Although his parents’ name was Harnett, he was registered in error as Hartnett on his birth certificate. In later life he declined to change this as his legal name was closer to the Irish Ó hAirtnéide. He grew up in the Maiden Street area of Newcastle West, Co. Limerick, spending much of his time with his grandmother Bridget Halpin, who resided in the townland of Camas, in the countryside nearby. Hartnett claimed that his grandmother, was one of the last native speakers to live in Co. Limerick, though she was originally from North Kerry. He claims that, although she spoke to him mainly in English, he would listen to her conversing with her friends in Irish, and as such, he was quite unaware of the imbalances between English and Irish, since he experienced the free interchange of both languages. When he began school, he claims that he was made aware of the tensions between both languages, and was surprised to discover that Irish was considered an endangered language, taught as a contrived, rule-laden code, with little of the literary attraction which it held for him. He was educated in the local national and secondary schools in Newcastle West. Hartnett emigrated to England the day after he finished his secondary education and went to work as a tea boy on a building site in London.

Early writings

Hartnett had started writing by this time and his work came to the attention of the poet John Jordan, who was professor of English at University College Dublin. Jordan invited Hartnett to attend the university for a year. While back in Dublin, he co-edited the literary magazine Arena with James Liddy. He also worked as curator ofJoyce’s tower at Sandycove for a time. He returned briefly to London, where he met Rosemary Grantley on 16 May 1965, and they were married on 4 April 1966. His first book, Anatomy of a Cliché, was published by Poetry Ireland in 1968 to critical acclaim and he returned to live permanently in Dublin that same year.

He worked as a night telephonist at the telephone exchange on Exchequer Street. He now entered a productive relationship with New Writers Press, run by Michael Smith and Trevor Joyce. They published his next three books. The first of these was a translation from the Irish, The Old Hag of Beare (1969), followed by Selected Poems (1970) and Tao (1972). This last book was a version of the Chinese Tao Te Ching. His Gypsy Ballads (1973), a translation of the Romancero Gitano of Federico García Lorca was published by the Goldsmith Press.

A Farewell to English

In 1974 Hartnett decided to leave Dublin to return to his rural roots, as well as deepen his relationship with the Irish language. He went to live in Templeglantine, five miles from Newcastle West, and worked for a time as a lecturer in creative writing at Thomond College of Education, Limerick.

In his 1975 book A Farewell to English he declared his intention to write only in Irish in the future, describing English as ‘the perfect language to sell pigs in’. A number of volumes in Irish followed: Adharca Broic (1978), An Phurgóid (1983) and Do Nuala: Foighne Chrainn (1984). A biography on this period of Michael Hartnett’s life entitled ‘A Rebel Act Michael Hartnett’s Farewell To English’ by Pat Walsh was published in 2012 by Mercier Press.

Later life and works

In 1984 he returned to Dublin to live in the suburb of Inchicore. The following year marked his return to English with the publication of Inchicore Haiku, a book that deals with the turbulent events in his personal life over the previous few years. This was followed by a number of books in English including A Necklace of Wrens (1987), Poems to Younger Women (1989) andThe Killing of Dreams (1992).

He also continued working in Irish, and produced a sequence of important volumes of translation of classic works into English. These included Ó Bruadair, Selected Poems of Dáibhí Ó Bruadair (1985) and Ó Rathaille The Poems of Aodhaghán Ó Rathaille (1999). His Collected Poems appeared in two volumes in 1984 and 1987 and New and Selected Poems in 1995. Hartnett died from Alcoholic Liver Syndrome. A new Collected Poems appeared in 2001.

Eigse Michael Hartnett

Every April a literary and arts festival is held in Newcastle West in honour of Michael Hartnett. Events are organised throughout the town and a memorial lecture is given by a distinguished guest. Former speakers include Nuala O’Faolain, Paul Durcan, David Whyte and Fintan O’Toole.[3] The annual Michael Hartnett Poetry Award of 6500 euro also forms part of the festival. Funded by the Limerick County Arts Office and the Arts Council of Ireland, it is intended to support and encourage poets in the furtherance of their writing endeavours. Previous winners include Sinéad Morrissey and Peter Sirr.[4]

During the 2011 Eigse, Paul Durcan unveiled a bronze life-sized statue of Michael Hartnett sculpted by Rory Breslin, in the Square, Newcastle West. Hartnett’s son Niall spoke at the unveiling ceremony.[5]

Publication History

- Anatomy of a Cliché (Dublin: Dolmen Press 1968)

- The Hag of Beare, trans. from Irish (Dublin: New Writers Press 1969)

- A Farewell to English (Gallery Press 1975)

- Cúlú Íde/ The Retreat of Ita Cagney (Goldsmith Press 1975)

- Poems in English (Dublin: Dolmen Press 1977)

- Prisoners : (Gallery Press 1977)

- Adharca Broic (Gallery Press 1978)

- An Phurgóid (Coiscéim 1983)

- Do Nuala, Foidhne Chuainn ( Coiscéim 1984)

- Inchicore Haiku (Raven Arts Press 1985)

- An Lia Nocht (Coiscéim 1985)

- A Necklace of Wrens: Poems in Irish and English (Gallery Press 1987)

- Poems to Younger Women (Gallery Press 1988)

- The Killing of Dreams (Gallery Press 1992)

- Selected and New Poems (Gallery Press 1994)

- Collected Poems (Gallery Press 2001)

- A Book of Strays (Gallery Press 2001)

Select translations

- Tao: A Version of the Chinese Classic of the Sixth Century (New Writers Press 1971)

- Gypsy Ballads: A Version of the Romancero Gitano of Frederico Garcia Lorca (Newbridge: Goldsmith Press 1973)

- Ó Bruadair (Gallery Press 1985)

- Selected Poems of Nuala Ní Domhnaill (Gallery Press 1986)

- An Damh-Mhac, trans. from Hungarian of Ferenc (Juhász 1987)

- Dánta Naomh Eoin na Croise, translation from St. John of the Cross (Coiscéim 1991)

- Haicéad (Gallery Press 1993)

- Ó Rathaille: The Poems of Aodhaghán Ó Rathaille (Gallery Press 1999)

- Translations (Gallery Press 2002)

References

Further reading

- Remembering Michael Hartnett Edited by Stephen Newman and John McDonagh; (November 2005); Four Courts Press; ISBN 978-1-85182-944-6

- ‘Wrestling with Hartnett’, by Eamon Grennan; in The Southern Review, Vol. 31, no. 3; (June 1995); p. 659

- Lawlor, James. “Are these my people?’ A Study of Contemporary Working-Class Irish Poetry M.A Diss. Queen’s University Belfast. 2010. Print.

- ‘Male and Heretic: Michael Hartnett and Masculine Doubt’, by Val Nolan; lecture delivered to Southern Voices: A Symposium on Contemporary Munster Poetry in English; University College Cork; (May 2008)

- Notes From His Contemporaries: A Tribute to Michael Hartnett. Photographs by Niall Hartnett; (May 2009/ March 2010); Niall Hartnett.com/ Lulu Inc.

- Purchase Book at Niallhartnett.com

- Official Michael Hartnett website

- Michael Hartnett’s page at Wake Forest University Press

- Hartnett at Irish Writers Online

- Mark Lonergan’s essay on Michael Hartnett’s “Inchicore Haiku”

- Michael Hartnett file at Limerick City Library, Ireland

- I Live in Michael HartnettI Live in Michael Hartnett (Revival Press 2013) ISBN 978-0-9569092-2-0 Poems in tribute, featuring work of Seamus Heaney, Eavan Boland, Paula Meehan, Brendan Kennelly . Edited and introduced by James Lawlor with foreword by Joan Mac Kernan

- “A Rebel Act: Michael Hartnett’s Farewell to English” Pat Walshe. (2012) Mericier Press.

Stair na hÉireann | History of Ireland